Introduction

Revised 30 October 2022

The standard of living in under developed nations is substantially lower than that in developed nations. There is an ethical issue here. If growth in material consumption were to cease in all nations, then under developed nations would be locked into a lower standard of living. There is undeniable empirical evidence of increasing global and national inequality. The share of the pie for the poor has substantially declined over the last 30 years. As of 2014, the top 1% of income accounts for 10% of the total income in advanced economies (Piketty, 2014). In the United States the top 10% has an income of close to nine times that of the bottom 10%.

Inequality is more dramatic when the wealth of the rich and poor are compared. Wealth is defined as the net worth of assets in the form of property and real assets less liabilities. In 2017, the richest top 1% of the world population owned 50% of global wealth (Credit Suisse, 2018). Economic growth has improved standards of living, but has also resulted in greater inequality. On ethical grounds, material consumption per-capita should be shared equally between nations and within nations. Higher standards of living tend to be accompanied by lower total fertility. If the rich nations were to assist the poor nations to raise their standard of living, then the world population would grow more slowly on its path to Zero Population Growth

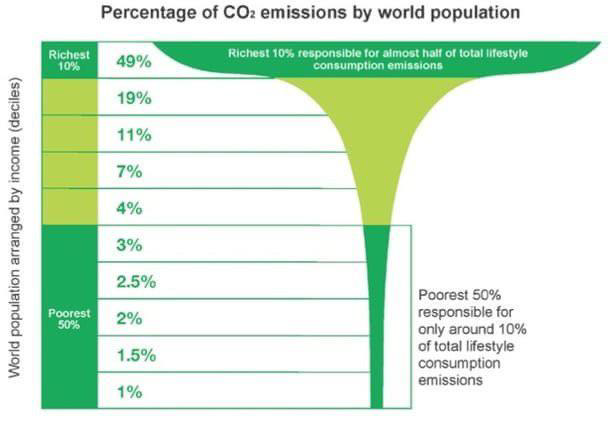

The mushroom graphic in Figure 1 shows the disproportionate consumption by the wealthy. In 2015, the richest 10% of people in the world, and that includes New Zealanders, were responsible for 49% of CO2 emissions, while the poorest 50% of people in the world were responsible for only around 10% of total lifestyle consumption emissions. An immediate 50% reduction in emissions by the richest 10% in the world would have reduced global CO2 emissions to 75% of levels in 2015. A 75% reduction would have reduced global emissions to 62.5% of levels in 2015.

Figure 1: Disproportionate Consumption by the Wealthy (Oxfam 2015)

INEQUALITIES IN CONSUMPTION AND GREENHOUSE GAS EMISSIONS BETWEEN COUNTRIES

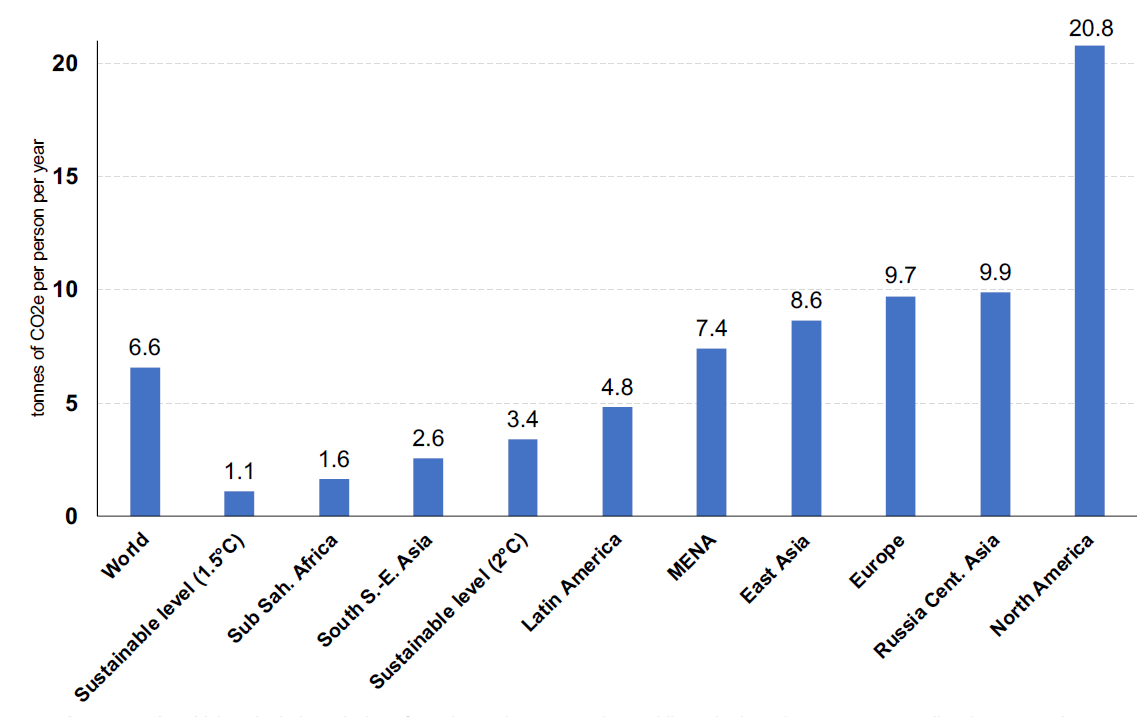

The extent of Inequalities in consumption and emissions of greenhouse gas equivalents (CO2e) between countries is shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Average carbon emissions across the world in 2019 (Chancel 2021)

According to Lucas Chancel (2021), the annual sustainable budget compatible with the 1.5°C limit is 1.1 tonne of CO2e per capita. This value is about six times less than the current global average. The annual sustainable budget compatible with the +2°C temperature limit is 3.4 tonnes per capita.

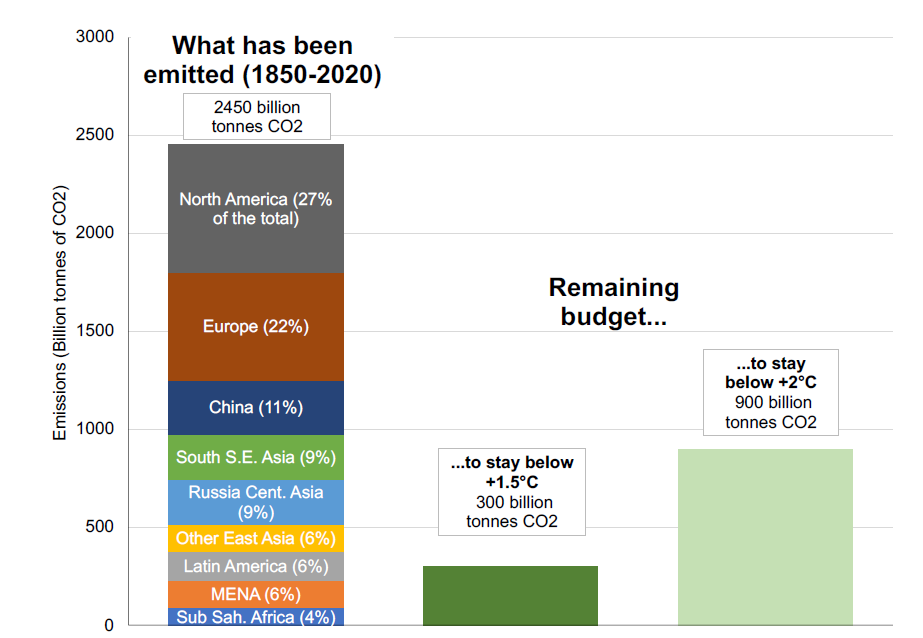

Figure 3 shows historical emissions from 1850 t0 2020 for different global regions.

Figure 3: Historical emissions versus remaining carbon budget (Chancel 2021)

INEQUALITY BETWEEN INDIVIDUALS AT THE WORLD LEVEL

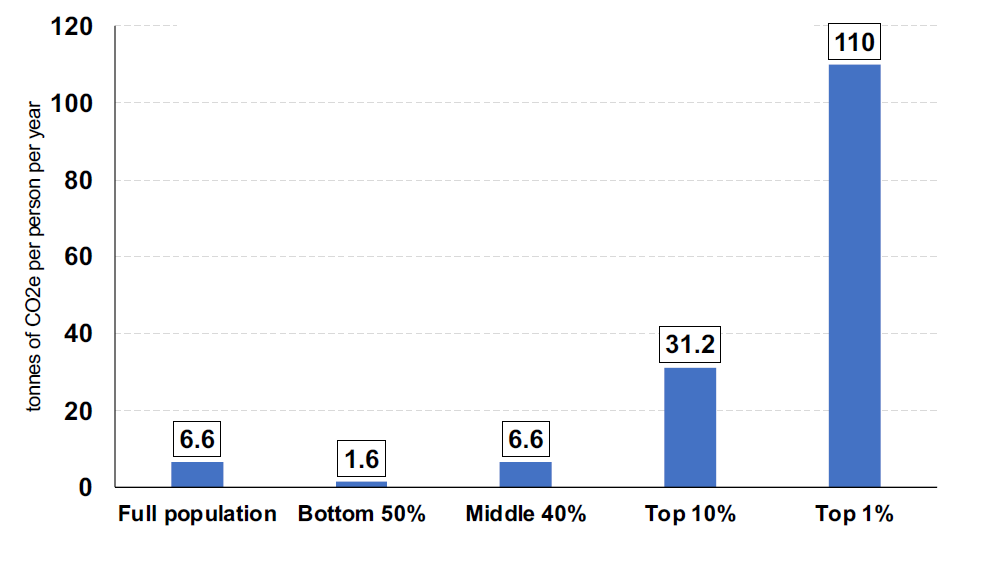

Figure 4 shows the inequality of carbon emissions between individuals at the world level.

Figure 4: Average per capita emissions by group in 2019 (Chancel 2021)

In 2019, the global bottom 50% emitted on average 1.6 tonnes per capita and contributed 12% of the total emissions. The middle 40% emitted 6.6 tonnes on average, making up 40.4% of the total emissions. The top 10% emitted 31 tonnes (47.6% of the total emissions) and the top 1% emitted 110 tonnes (16.8% of the total emissions).

INEQUALITY OF CONSUMPTION AND GREENHOUSE EMISSIONS WITHIN NATIONS

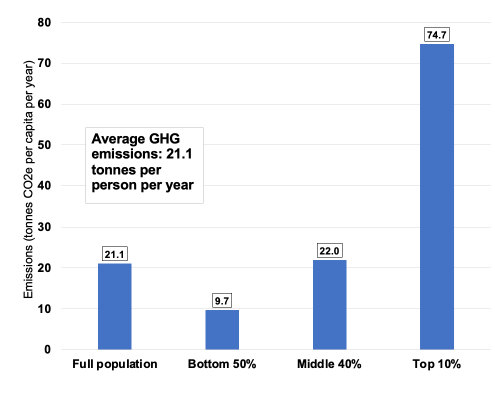

Inequality also exists within nations. Figure 5 shows per capita emissions by income group in the United States as an example

Figure 5: Emissions inequality and per capita emissions in the US 2019 (Chancel 2021)

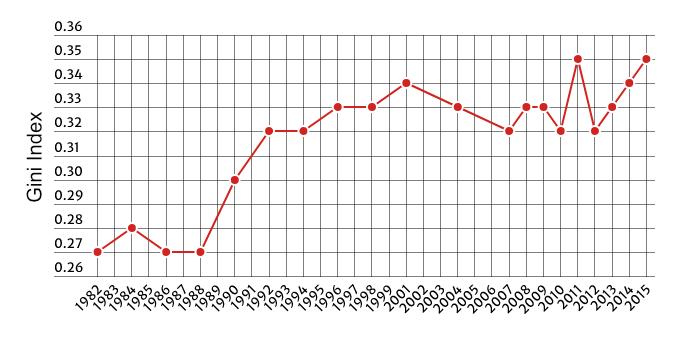

The Gini index measures the extent to which the distribution of income or consumption expenditure among individuals or households within an economy deviates from a perfectly equal distribution. A Gini index of 0 represents perfect equality, while an index of 100 implies perfect inequality. Figure 6 shows the increase in household inequality in New Zealand from 1982 to 2016 using the Gini index.

Figure 6: Gini index measure of household inequality in New Zealand 1982-2015 (Stats NZ)

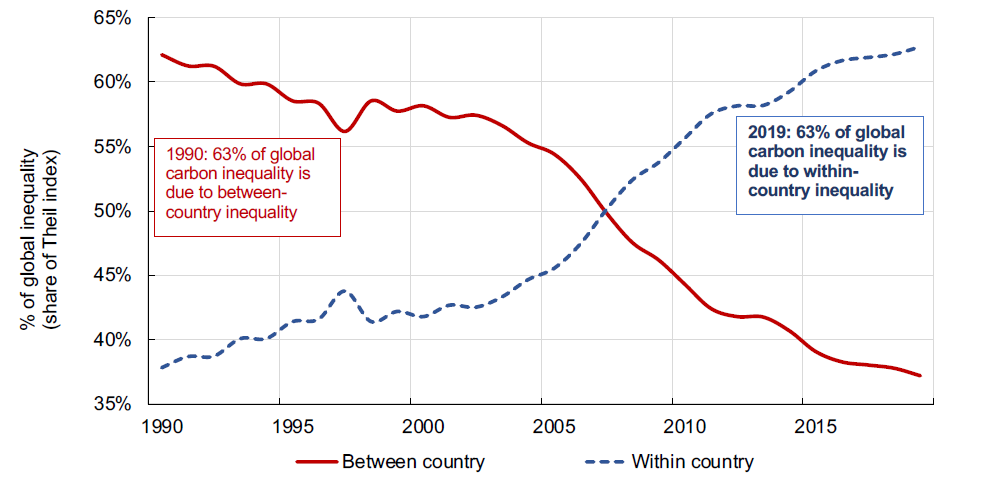

Figure 7 shows global carbon inequality between countries and within countries from 1990 to 2019.

Figure 7: Global carbon inequality between countries and within countries 1990 to 2019 (Chancel 2021)

The vertical Y-axis show the percentage of global inequality using the Theil index which is used to measure economic inequality. The Theil index measures a distance away from the ideal egalitarian state of everyone having the same income. Greater levels of inequality are indicated by higher percentages of the Theil index. In 1990, most global carbon inequality (63%) was due to differences between countries.

Carbon emission pledges made at the 2015 Paris Agreement are typically expressed in aggregate emissions percentage reductions from a base year. These pledges can be expressed in terms of emissions per capita at a certain time to make better sense of what they imply. These targets do not represent what must be done in order to keep emissions below 1.5 or 2°C. Official commitments do not add up to meeting the 2°C objective, much less to meeting the 1.5°C target.

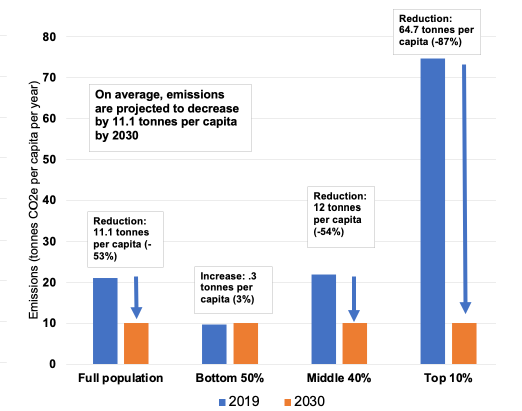

Figure 8 shows an example of necessary reductions in consumption and emissions of CO2e by income group to stay within this target.

Figure 8: Emissions by group versus a 3.0 tonne CO2e per capita climate target by 2030 in the US (Chancel 2021)

.

All actions to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions involve reductions in consumption. Material consumption includes consumption of minerals, fossil fuels, and ecological systems which provide both food and resources. Those on low incomes have less ability to further reduce their carbon footprints than those on higher incomes. Figure 8 shows the extent that people in the United States need to reduce their consumption to attain a 3.0 tonne CO2e per capita carbon footprint. The bottom half of the population in the United States is already 3% below the target. The middle 40% and top 10% would need to reduce the CO2e emissions by 54% and 87% respectively to achieve the target of 3.0 tonnes of CO2e emissions by 2030. According to Lucas Chancel (2021), the bottom 50% of other rich countries are already below a 2030 target of 3.0 tonnes of CO2e per capita, or close to it. The figure demonstrates that the key to global reductions in greenhouse gas emissions is for all citizens of the world to participate equally. If those on higher incomes do not participate, then the efforts of all others will be in vain. Participation can be voluntary or enforced by our institutions. Failing that, nature itself in due course will enforce a reduction in consumption.

Section to be added to

Sources (to be used):

Dabla-Norris, E., K. Kochhar, N. Suphaphiphat, F. Ricka, and E. Tsounta. Causes and Consequences of Income Inequality: A Global Perspective, IMF Discussion Note, International Monetary Fund, 2015.

Piketty, T. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge Massachusetts, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2014.

Sayer, A. Why We Can’t Afford the Rich. Bristol, Policy Press, University of Bristol, 2015.

Shorrocks, A., J. Davies, and R. Lluberas. Global Wealth Report 2018, Credit Suisse, 2018.

Wilkinson, R. and K. Pickett. The Spirit Level: Why Greater Equality Makes Societies Stronger, New York, Bloomsbury Press, 2009.