Decoupling

Revised 2 February 2023

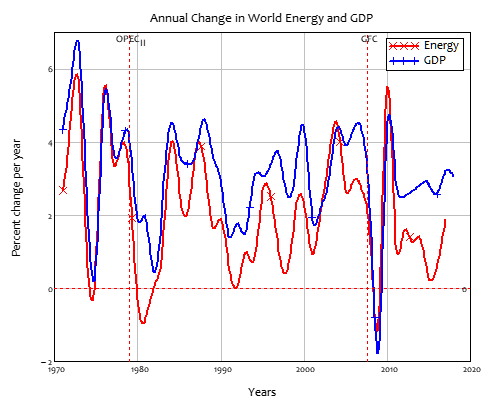

There are claims that reductions in material production and consumption can be implemented by decoupling growth in the economy from that of energy and materials. Figure 1 shows annual changes in world energy and GDP. The correlation coefficient is a high 0.83.

Figure 1: Annual Changes in World Energy and GDP (Keen 2021)

This high correlation is not unexpected because any form of economic activity, both good and bad, requires the use of both energy and materials. The energy intensity of many products and services can be reduced and their use of energy can also be reduced, but there are also physical and thermodynamic limits to what can be achieved (Jackson, 2009). Absolute decoupling of an economic system from the use of energy and materials is a physical impossibility.

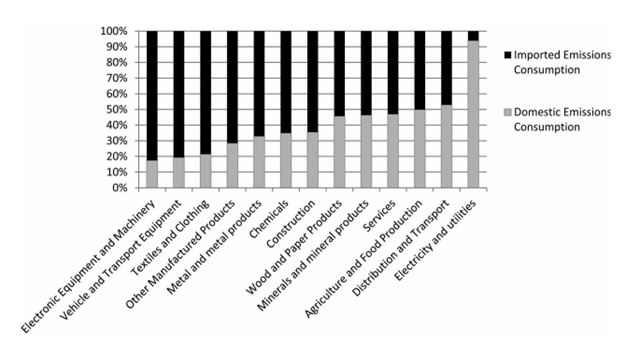

Relative decoupling of GDP from energy and materials is possible, but limited due to physical and thermodynamic limits. There are thermodynamic limits to the possible efficiencies of energy production by renewables which we are already close to achieving. Photovoltaic panels and wind turbines are good examples. Claims of relative decoupling in some countries have been largely due to not taking into account the embodied energy of imported goods. Figure 2 shows an example of the extent that emissions of consumption within a country is based on both domestic and imported generation of emissions. Many countries have shifted their factories to China where factory production emits greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. The products are then exported from China to other countries for consumption. Reductions in both domestic and imported consumption within each country are necessary to mitigate the impact of climate change.

Figure 2: Percentage pf GHG emissions in the UK associated with different groups (Barrett et al., 2011)